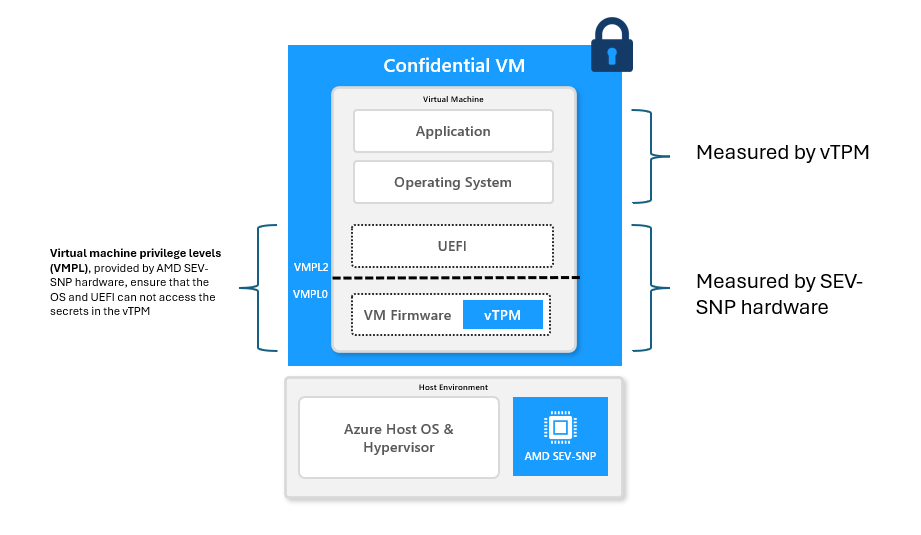

In a previous post, I explained that the direction most Confidential Computing deployments are converging toward is to reintroduce the TPM abstraction inside the Confidential VM itself. Rather than relying on a physical TPM, the goal is to expose a TPM interface from within the TEE.

This design choice is largely pragmatic. It enables a lift-and-shift model for existing operating systems and workloads that already depend on TPMs for measured boot, disk encryption, and remote attestation. At the same time, it preserves the familiar TPM security guarantees while replacing physical trust assumptions with hardware-enforced isolation.

Image credit: Microsoft

Image credit: Microsoft

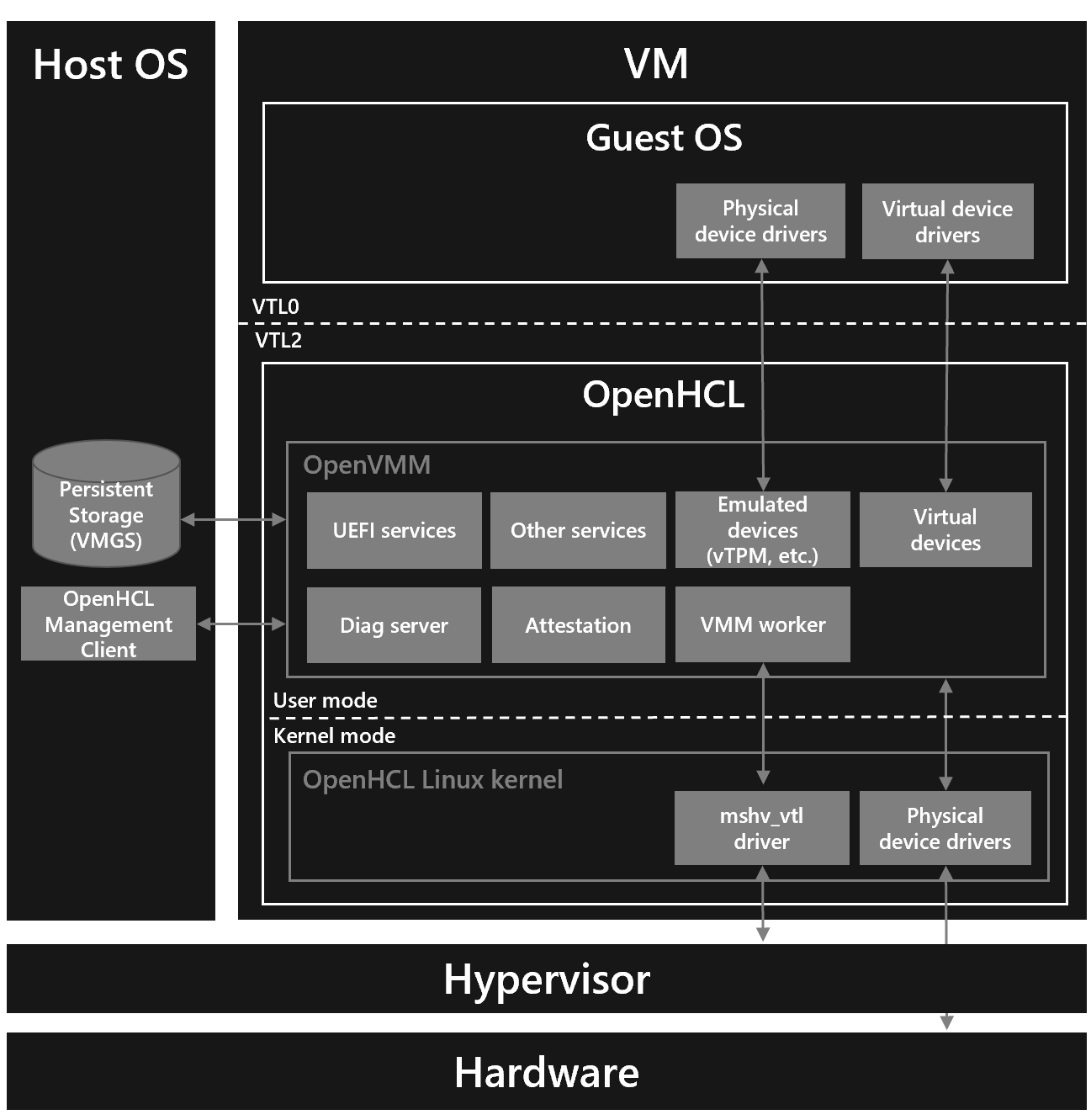

To make this work, the vTPM cannot run inside the guest kernel. Instead, it is hosted by a small, highly privileged runtime that sits above the guest OS. Two concrete examples of this approach are COCONUT-SVSM in the AMD SEV-SNP ecosystem and OpenHCL in Microsoft’s confidential computing stack.

These components are sometimes called firmware, but that label hides an important detail. They are not just boot-time code like UEFI. They are resident runtimes, measured at VM launch, executing at a higher privilege level than the guest kernel, and entered whenever the VM performs a confidential-computing exit. In practice, they act as paravisors, hosting security-critical services such as memory validation, device mediation, and the vTPM itself.

Image credit: Microsoft

Image credit: Microsoft

A question that puzzled me for a while

Once you accept that the TPM abstraction belongs inside the CVM, a subtle problem appears.

If the vTPM is part of the trusted computing base, then its build must be reproducible. Otherwise, remote attestation loses its meaning: you cannot verify that the code you audited is the code that is actually running.

At the same time, a TPM is defined by the presence of an Endorsement Key (EK). That key must be unique to each TPM instance, must never be disclosed in private form, and serves as the root of identity for TPM credentials and attestation keys.

At first glance, these requirements appear incompatible. How can a reproducibly built vTPM binary “contain” a unique EK? And if the EK is generated dynamically, how can a remote verifier trust that this EK belongs to a genuine vTPM rather than to a compromised guest kernel impersonating one?

A quick reminder: what the EK is actually about

The EK is not just another TPM key. It is the identity anchor of the TPM. Everything else, attestation keys, quotes, credentials, derives its trust from the assumption that the EK private key is held only by a genuine TPM.

On physical hardware, that trust comes from manufacturing: the EK is injected at the factory and certified by the vendor. In a virtual TPM, there is no factory and no physical chip. The question becomes: what replaces that root of trust?

Why the naïve approach fails

Assume a realistic threat model where the guest kernel and disk are untrusted.

If the kernel is compromised, it can fabricate PCR values, invent TPM quotes, and generate arbitrary key pairs while claiming they are TPM keys. If the verifier has no prior trust anchor for the EK (no certificate chain, no pinned public key) then such claims are indistinguishable from legitimate ones.

Simply generating an EK at runtime is therefore insufficient. Without a way to bind that key to something the verifier already trusts, any kernel can pretend to be a vTPM.

Reproducibility versus identity: separating concerns

The resolution starts by separating two ideas that are often conflated.

Reproducibility applies to code, not to instance-specific secrets. The vTPM binary and the paravisor hosting it must be reproducible so their measurements can be verified. The EK is runtime state, generated after launch, and does not belong in the build output.

That separation removes the apparent contradiction, but it leaves one remaining question: how does a remote verifier learn that this runtime-generated EK was created inside a specific, attested vTPM implementation?

This is where key binding enters the picture.

The key binding mechanism

Modern confidential-computing attestation formats, such as SEV-SNP reports and Intel TDX quotes, include a small field commonly called REPORT_DATA. This field is covered by the hardware signature and therefore becomes part of what the verifier ultimately trusts.

The crucial point (and the source of my original confusion) is who actually controls this field.

Although the guest kernel may initiate the attestation request, the request is handled by the paravisor. The kernel does not talk directly to the hardware attestation engine. Instead, it exits into the paravisor, and execution continues there. From that point on, the kernel is no longer running.

This means that whatever the kernel might attempt to place into REPORT_DATA is not authoritative. The paravisor interprets the request, computes the data it wants to bind, and places its own value into the attestation structure. Any kernel-supplied value is ignored or overwritten.

With that in mind, the binding process becomes straightforward.

At runtime, the vTPM generates its EK (or, more commonly, an Attestation Key derived from it). The private key never leaves the paravisor-controlled environment. When an attestation is requested, the paravisor computes a binding value (typically a hash over the public key and a verifier-provided nonce) and writes that value into the REPORT_DATA field.

The hardware then signs an attestation report that covers the paravisor measurement, security attributes, and this REPORT_DATA field. When the verifier checks the report, it verifies not only that the paravisor is the expected one, but also that the reported binding matches the vTPM key it was given.

At that point, the verifier can conclude that this key was generated by a vTPM running inside a specific, attested paravisor instance.

Why a compromised kernel cannot fake this

Even though the kernel triggers the attestation request, it is not part of the signing path. Once the VM exits, execution moves into the paravisor, which controls both the binding computation and the attestation request to the hardware.

The kernel can relay messages, but it cannot inject its own key into the attestation, cannot modify the signed report, and cannot produce TPM quotes signed with the bound private key. Any attempt to fabricate vTPM evidence will fail either at attestation verification time or when TPM signatures are checked.

Conclusion

This design resolves the original paradox cleanly.

The vTPM and paravisor binaries remain fully reproducible and auditable. The EK is unique and secret, generated at runtime rather than embedded in the build. And trust in that EK comes not from preinstalled certificates, but from cryptographic binding to a hardware-attested execution environment.